Witches Have Always

Lived in Patriarchy:

Shirley Jackson’s Castle of Female Empowerment

Shirley Jackson’s Castle of Female Empowerment

︎︎ Year: 2016

Expressions in Study: American Gothic Literature, Psychoanalysis, Feminism

The gothic mode exposes

underlying fears and anxieties, revealing the return of “what is unsuccessfully

repressed” (Savoy 4). The sense of the ordinary becomes a societal construction

of what is deemed normalized and acceptable by society. In this sense, the

gothic mode unmasks what society represses beneath the realm of the normal.

Judith Butler describes gothic fiction as “compelling but unthematizable” (7),

a mode dedicated to illuminate the inexplicable while still remaining entirely

in an unexplainable space. In other words, that which is gothic “resists and

compels symbolization” (Butler 70) and it is precisely in this inexplicability

that unleashes a “pattern of anxiety of the Symbolic… [to show] the fragility

of our usual systems of making sense of the world” (Williams 70). If the

Lacanian Symbolic explains man’s formation of meaning, and introduces man into

a societally sanctioned law system by providing man with the relevant arbitrary

connections between signifiers and signifieds, then the gothic convention

destabilizes the acceptance of these connections as it “impl[ies] disorder in

the relations of signifiers and signifieds” (Williams 70). An American

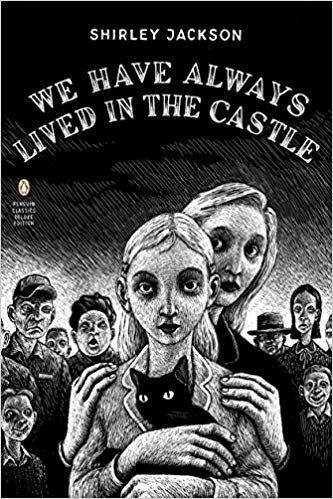

contemporary gothic revelation, Shirley Jackson’s 1962 masterpiece We Have Always Lived in the Castle valorizes

the disorderliness from this destabilization in normalized patriarchal society.

Published by Penguin Classics, illustration by Thomas Ott (2006)

Photography by Freestock

Jackson utilizes the

fear of the unknown and inexplicable, and exposes it as a societal anxiety, which

culminates in the realm of the abject. Existing as neither subject nor object,

the abject is that which is feared and thus repressed by societal order. Yet,

even in its arena of “banishment, the abject does not cease challenging its

master” (Kristeva 2). To be in abjection is to straddle along the fragile

boundaries between the Lacanian Real and Symbolic. To be the abject is to be

prohibited from any entrance into the Symbolic Order. If the abject is that

which is constantly repressed, then the gothic mode “enable[s] the narrativization

of [the] irrepressible Otherness” (Savoy 5). To be abject is not merely to

provide discomfort through the “slack boredom of repression” (Kristeva 2), but

it is the simultaneous attraction and repulsion that one feels towards the

abject that makes it so desirable yet threatening. When Mrs. Wright persists in

her interrogation about the Blackwood mass murder, she fulfills her sheer desire

of acquiring knowledge for her sole intent to gossip while remaining physically

threatened by Constance Blackwood’s potentially murderous action of spiking her

tea with poison. Jackson’s use of the gothic figure of the witch in Castle then becomes a response to a

highly dominant patriarchal and conservative culture. The witch-figure embodies

the unthematizable, a physical manifestation of the exclusion from the Symbolic

Order. In other words, the witch-figure exists in the space of the abject. Seen

as a “patriarchal perversion”, witchcraft is the woman’s ultimate “rebellion

against suppression” (Heinemann 22). Hence, the witch-figure inhibits any form

of meaning-making yet empowers itself by its sheer power of fear-instilling, thus

any attempt to assimilate it back into conventional society backfires

detrimentally.

Conventional explanations for the fear of witches amount to the fear of “women who were experts in the use of herbs, able to control their own fertility and unwilling to submit to a patriarchy” (Heinemann 19). In Castle, the Blackwood sisters seem to fulfill these requirements, but if anything, these seemingly threatening characteristics only point to the patriarchal society’s misogynistic tendency in attempting to control and dominate women. Not only does Castle express the post-World War II era’s “highly conservative, often stifling set of cultural and social expectations… in which troubled young women struggle to escape the control of domineering father figures” (Murphy 147), it also deconstructs all attempts in society’s construction of normalcy. Jackson’s Castle is an instinctual feminist reaction to the 20th century American conservative and patriarchal mindset. Therefore, by aligning the abjection of the witch with the Blackwood sisters, I argue that abjection in Castle can be read as a unique feminine state, which is to construe the abject as female rebellion against the Name-of-the-Father. In other words, patriarchy attempts to quell female power. I posit that in the use of the gothic trope, Jackson artfully crafts the witch-figure as the irreducible abject for any society, transgressing and destabilizing patriarchal society to reveal its repressed anxieties. Castle solves the difficulty of co-existence between the abject and the accepted by empowering the former in all its inexplicable glory. At once, the witch-figure resists any control from patriarchal normalized society and empowers herself in her command of fear.

Photography by Gregory Culmer

If that which is taboo

and repressed has a physical incarnation, it would take on the figure of the

witch. The witch, in other words, emblematizes the unrepressed: that which is

free to contravene the laws imposed by society. Merricat and Constance

Blackwood are metaphorical witches insofar as they are not true practitioners

of black sorcery nor satanic rituals. Evelyn Heinemann argues that the “image

of the witch is an imago, an internal image, containing personal aggressions”

(34), a perverse identification of the cohesive whole in the Lacanian mirror

phase. In other words, patriarchal society identifies the abject witch-figure as

the horrific Other due to its “projective identification… [of its] aggressions

and feelings of persecution” (Heinemann 34) onto the Blackwood sisters. Hence,

by assigning the Blackwood sisters these qualities of aggressions and repressed

desires, patriarchy metaphorically defines them as witches. Therefore, the

witch is “flatly driven” (Kristeva 2) away by the superego – patriarchal

society – as an act of stabilizing the status quo. In order to maintain the

balance between the law and the taboo, patriarchy has to either oppress the abject-as-witch

or annihilate her.

The Blackwood sisters’

susceptibility to such a prejudiced projection stems from their complete

departure from patriarchy. Being the “survivor of the most sensational poisoning

case of the century” (32), Uncle Julian “personally prefer[s] to chance the

arsenic” (36) as opposed to eating the deceased Mrs. Blackwood’s cooking which

suggests that she was truly a terrible cook. Yet, tradition shows that all

Blackwood women “had made food and had taken pride in… [their] cellar” (42),

indicating that Mrs. Blackwood had failed to conform to this great expectation

by virtue of not fulfilling the characteristic of being an able cook. The

cellar is the amalgamation of rule-abiding orderliness and conformity to social

conventions. Filled with jars of jam and preserves, the cellar symbolizes the

domestic woman’s self-preservation of her identity amidst the gender coded

space of the kitchen. Instead, Merricat states that her mother had a profound

love for Dresden figurines. In other words, Mrs. Blackwood shares a strong

appreciation for the ornate rather than satisfying the patriarchal dictation of

“adding to the great supply of food” (42). In this sense, the female tradition

in the Blackwood lineage seems to deviate from patriarchal orderliness the moment

Mrs. Blackwood failed to perform her gender specified role.

Photography by Callie Gibson

The poisoning of the

Blackwood family seems to be the icing on the cake when it comes to the

decision to position the Blackwood sisters as the taboo witch-figures in

society. When Merricat says that “the people of the village have always hated

[them]” (4), it already suggests the society’s latent repulsion from the

Blackwoods. Despite being acquitted of murder, the villagers still see Constance

Blackwood as the murderer of her family. The fact that the female has the

ability to commit murder immediately removes her from the safe haven of the

domestic. Put differently, the female becomes a threat. Once, the villagers had

no qualms taunting the Blackwoods at their doorstep as they “came to pound at

the house”, demanding that they had the “right to see [Constance] … [because

she had] killed all those people” (56). Society’s intrusion into the private

space of the Blackwood mansion indicates their prejudice against the Blackwoods,

and their surmounting fear of the Blackwood sisters. The remaining Blackwoods

serve as living reminders of potential danger to the society precisely because

the master-figure, Mr Blackwood, has been destroyed. Scratching beneath the

surface, this fear points to the tension from the castration complex. If

anything, the survival of Uncle Julian reminds the village not only of a failed

patriarch, but also the dominance of female power in the Blackwood household.

In other words, Uncle Julian lives in the abject space of the Blackwood house

with the abject witch-figures, Merricat and Constance. Julian Blackwood lived

off his brother, managed to survive the arsenic poisoning, but he is ultimately

rendered physically and mentally invalid. Thus, if the Blackwood sisters

possess tremendous power to overthrow male dominance in the house, then they

embody the ultimate transgression from the “symbolic matrix” (Lacan 2) of law

and order.

Click here to read the full article >

Click here to read the full article >

© Annabel Lee 2019